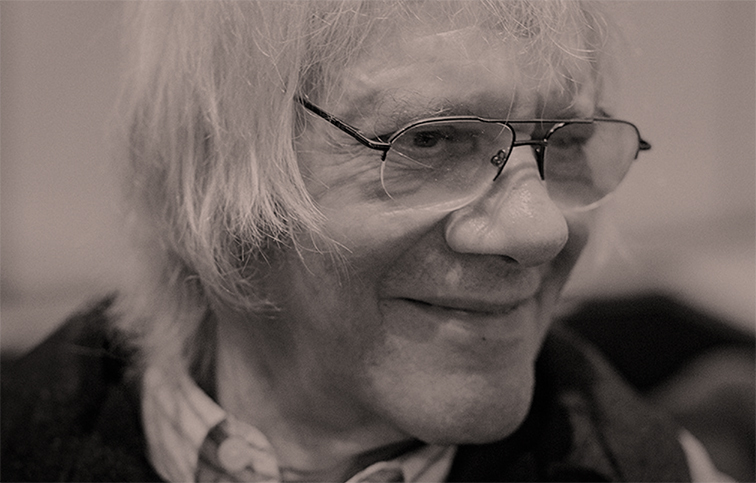

Cecil Taylor was one of the most uncompromisingly gifted pianists in jazz history, utilizing a nearly overwhelming orchestral facility on the piano. While his work elicited controversy almost from the start, Taylor’s artistic vision never swayed.

At his mother’s urging he began piano studies at age five. He later studied percussion, which undoubtedly influenced his highly percussive keyboard style. At age 23 he studied at the New England Conservatory, concentrating on piano and music theory. He immersed himself in 20th-century classical composers, including Stravinsky, and found sustenance for his jazz proclivities in the work of Lennie Tristano and Dave Brubeck. Later Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, and Horace Silver began to influence his playing. By 1956 he was working as a professional, taking a prolonged engagement at New York’s Five Spot Cafe, recording his first album, Jazz Advance, and making his Newport Jazz Festival debut.

Playing in this style—an aggressive near-assault on the piano, sometimes breaking keys and strings—presented challenges in terms of finding steady work. Taylor struggled to find gigs for most of the 1950s and 1960s, despite being recognized by DownBeat magazine in its „New Star” poll category. He eventually found work overseas, touring Scandinavian countries during the winter of 1962-63 with his trio, including Jimmy Lyons on alto saxophone, and Sunny Murray on drums. His approach had evolved to incorporate clusters and a dense rhythmic sensibility, coupled with a sheer physicality that often found him addressing the keyboard with open palms, elbows, and forearms. His solo piano recordings are some of the most challenging and rewarding to listen to in all of jazz.

His work as a pianist and composer gained much-needed momentum in the 1970s and beyond, as touring and recording opportunities increased, largely overseas, though finding regular work for his uncompromising style of music remained a struggle. Throughout his career, he worked with many important, like-minded musicians, including Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Steve Lacy, Sam Rivers, Max Roach, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and a host of European and Scandinavian musicians. In 1979, he performed at the White House, and he received numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973 and a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in 1991. His influence on the avant-garde, especially of the 1960s and 1970s, in terms of performance and composition, is enormous.